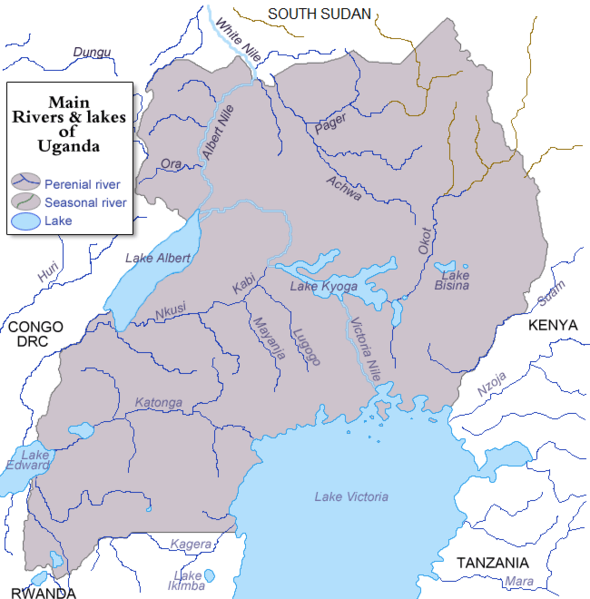

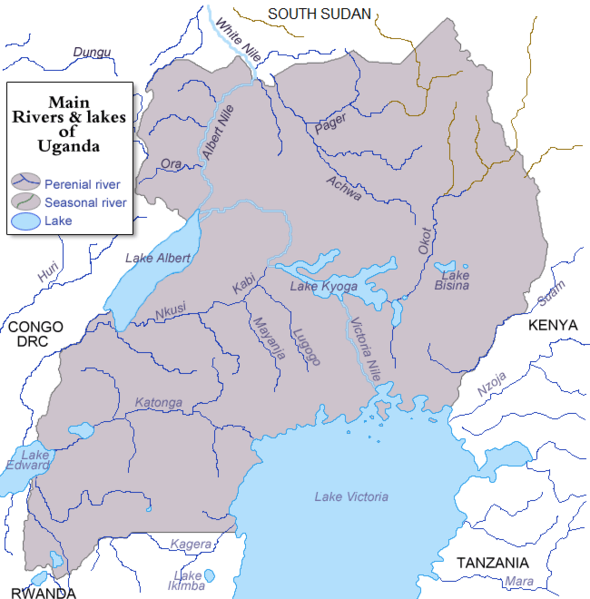

I spent most of this past week out in Amolatar town, headquarters of Amolatar district, which is located on a peninsula that juts out between two lakes on the Victoria Nile. This is a pretty remote area: it took us around 4 hours to drive there from Lira, which is itself a 5 or 6 hour drive from Kampala. One of the most popular ways of getting to Amolatar is to take a ferry across the lake. In this map from Wikipedia, Amolatar is the peninsula snaking down into what is marked Lake Kyoga (the upper part of the lake is technically Lake Kwania):

On the other hand, compared to other places I’ve been to in rural Africa, Amolatar town is pretty built up. While most of the way here was along dirt roads, they’re decently maintained (lots of washboarding but limited potholes). The town has electricity, and I could get internet on my iPhone via MTN. More of a pleasant surprise was that it also has piped water and sewage. Here’s a picture of what Amolatar town looks like:

The biggest limitation to Amolatar’s development that I noticed was actually its dearth of snack foods. I was working long hours, involving lots of manual labor (moving around supplies for the project) and often wanted small snacks to keep me going, or things to eat after the restaurants had closed for the night. But the shops in Amolatar sold almost no snack foods: just two kinds of basically-flavorless biscuits* enticingly branded “Glucose”, and one or two kinds of candy. At first I thought this was due to a strange, non-representative sample, but I then actually went to every single shop in Amolatar when I thought the project was going to run short of pencils. Not only were there no savory snacks on sale in the whole town, nobody even seemed to know what the word “crisps”** meant. I found this a strange contrast with Southern Malawi, where even in very small and remote villages there is a far wider selection of available snacks, including multiple savory options.

My theory for Amolatar’s peculariar lack of snacks comes down to the available options for actual food. Lots of the Ugandans I interact with, if they hear that I’ve also spent time in Malawi, want to know which country I like better. There’s obviously no general answer to this question: I’ve only been to a small part of each country, and they differ in countless ways, big and small. But one area where Northern Uganda clearly does better than Southern Malawi is in terms of food: simply put, in Amolatar I could get everything I ate in Jali, but also a whole bunch of other things. The diet in Southern Malawi is absolutely dominated by maize, eaten in the form of nsima (sort of like a thicker version of grits). In Northern Uganda, they eat that too, but also a wide range of other carbs, from matooke (a kind of plaintain) to nsima-like foods made with millet, to sweet potatoes. This region also has more variety in terms of the protein people eat, as well as more sauces and stuff I can’t even really place (boyo, for example, is a something between a sauce and a standalone carb that is made of peanuts and greens and goes amazingly well with rice).

That’s far from the end of the story. Malawi has the best hot sauces of anyplace I’ve ever been to. Beyond their amazing national champion brand, Nali***, there are other nationwide brands of hot sauce as well (Osman Foods makes another great one). Lots of restaurants also make their own artisanal hot sauces, and there are great small batch producers that produce sauces for sale, along with people growing their own heritage varieties of the bird’s eye pepper for people to add directly to their food. Uganda, meanwhile, has a single hot sauce brand that I’ve encountered, called Top Up, and it’s pretty much terrible. This is intimately related, I think, to the limited variety in food: if there are lots of options for dinner, it’s less worthwhile to invest in ways of (literally) spicing it up. Likewise, expanding your basic menu of food options is less worthwhile if you have a kickass hotsauce to throw on your food.

The same logic probably applies to snacks: tasty snack foods and tasty meals are, to some extent, substitutes in consumers’ utility functions. Given the cost and risk of bringing in new goods and trying to develop markets for them, Northern Uganda and Southern Malawi are stuck in different equilibria in the markets for snack foods and condiments. This leaves consumers in a tough spot: if the market could support the initial cost of bringing in more variety, I am sure that Malawians would like eating more different kinds of starch, and that Ugandans would come to appreciate a decent hot sauce – just as Americans have grown to enjoy a wide variety of ethnic foods in the last couple of decades.

* In the British sense – to Americans they are cookies.

** Chips, for Americans.

*** Lest you think I am just throwing Malawi a bone here, I should note that I literally bring cases of Nali home with me every time I come back from Malawi, and carefully dole them out to friends and family as patronage. It’s that good.