I recently came across this post about a video that raises the question “Who made my clothes?”

The video, started by an organization called Fashion Revolution, suggests an answer: young women like Manisha, who are miserable, and whom you can help by refusing to by the t-shirts they make and instead donate.*

But wait a second – who did make my clothes? Specifically, who are the people in the video who (it is suggested) made the t-shirts being sold? The only people with any agency in the video are the westerners who are choosing not to buy the shirts. The garment workers appear only in still photos in which they appear harrowed and fearful. They don’t do or say anything.

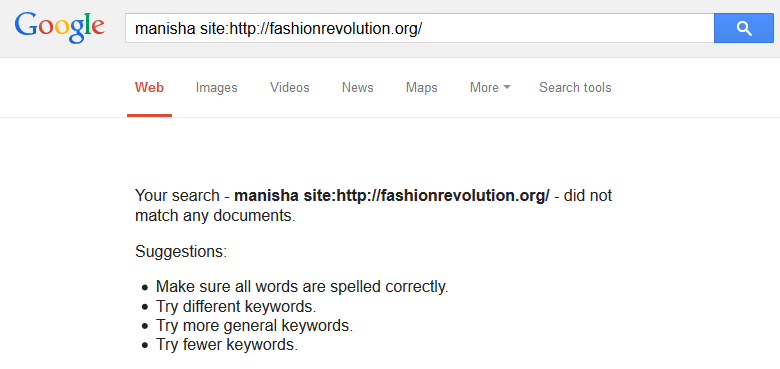

Who is Manisha? Why does she work in this factory? Does she support the idea of consumers refusing to buy the clothes she is paid to make? She doesn’t say anything in the video, and if Fashion Revolution gives her a voice or an identity at all, they don’t make it easy to find on their website:

I looked through the site’s blog, and didn’t see anything written by employees in the garment factories featured in the video. There are some quotes from people employed by garment makers that Fashion Revolution deems socially conscious, but nothing about the folks whose lives we are ostensibly trying to change. They appear only as a way to manipulate viewers of the videos. Fashion Revolution shows them to us – I want to know who they are and what they think about this campaign. I want to know why they work in these jobs, and what they would do instead if the jobs didn’t exist.

Fortunately, there is a way to learn about those questions. Planet Money conducted an epic 8-part investigation into how some t-shirts they bought were made (I previously mentioned this series in this post). In the episode “Two Sisters, a Small Room and the World Behind a T-Shirt” the producers learn that two of the garment workers who produced their shirts are a pair of sisters from Bangladesh named Shumi and Minu – and then they travel to Bangladesh, meet Shumi and Minu, and talk to them about their lives and their careers. Bad work conditions do come up, but so do many other problems and concerns and joys and triumphs in their lives. The followup to “who made my clothes?” shouldn’t be “let’s stop buying them” but “what do the human beings who made my clothes see as their problems, and how can we help?”

*There is no evidence from Fashion Revolution’s donation page that the money is actually going to Manisha or any of the other garment workers in the video. Instead, it sounds like the donations are going to raising awareness about the issue. That’s probably fine, but do the donors in the video understand that? Or do they think they are directly helping Manisha?

1 thought on “Garment workers are people, not props for your viral video”