A few weeks after I described my endeavors to figure out why people were always saying “which” (“ati”) around me, I managed to find the stem of the verb “kuti” in my hardcopy of Paas’s English-Chichewa/Chinyanja dictionary. This is evidently not just an aspect of Nyanja slang – it’s a legitimate word with its own entry. I’m going pay attention to see how much I hear it used in the central (Chewa-speaking) region next time I am up there.

Why did I have to learn the word through my field staff the first time? First off, the verb stem, “-ti”, is just two characters long, below the limit needed to search for it online. Second, kuti/-ti means at least half a dozen different things, depending on the context. Some examples:

1) Which (ati/liti/etc. with the prefix changing according to the noun class)

2) Where (kuti, “in which area/direction”/pati, “on which spot”/muti, “in which room”)

3) That (kuti)

4) Isn’t that right?

5) To say

6) To think

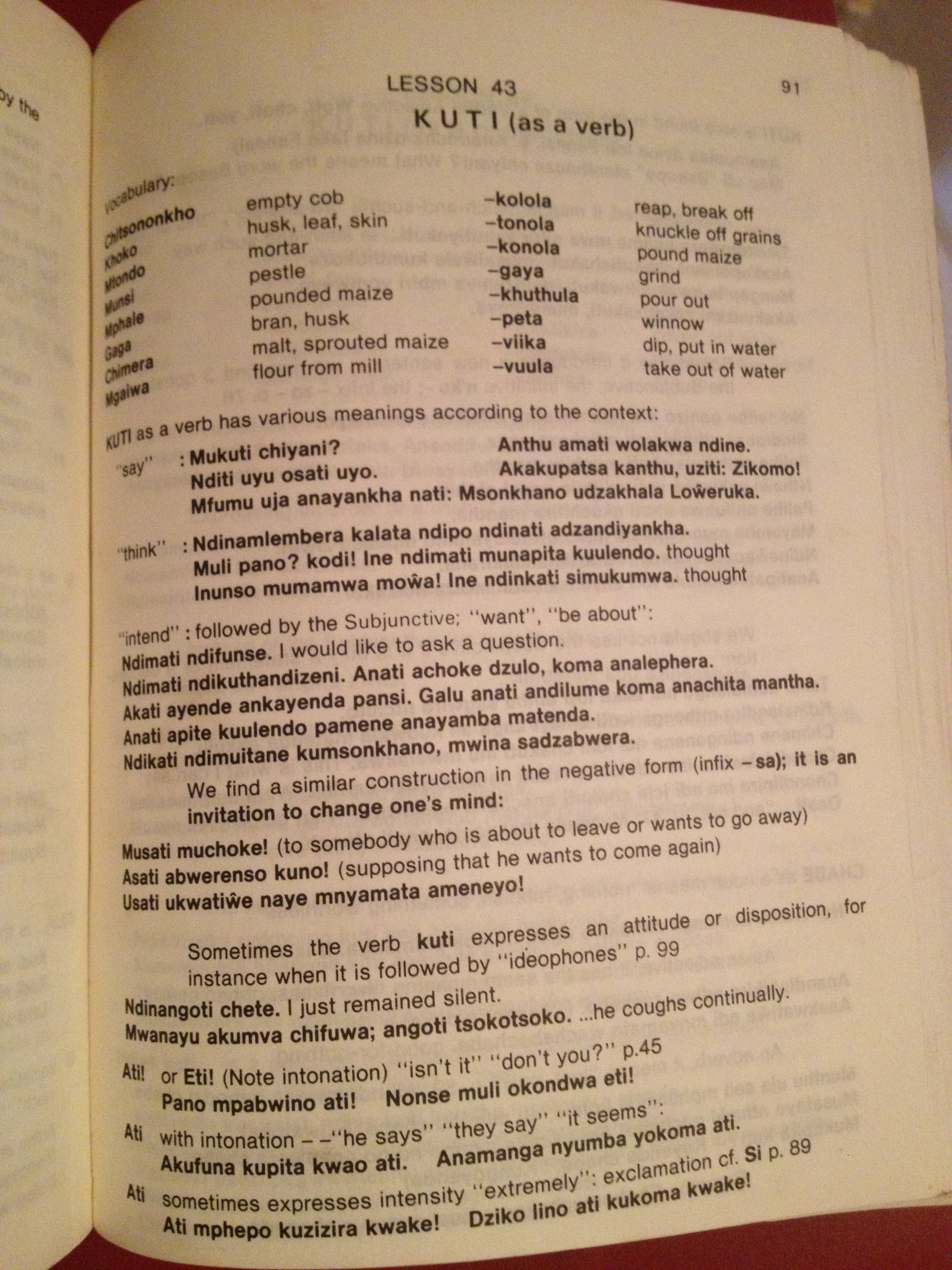

I got lead astray by definitions 1 and 4, when I wanted #5. A book I have called Chichewa Intensive Course by Fr. N. Salaun actually has a whole section dedicted to the various meanings of kuti in its verb form alone:

Homonyms are pretty common in Chichewa. One of my employees likes to say thatit’s not a rich language, but that’s a narrow view. Even if the vocabulary is limited (I don’t know enough of the language to be able to say) the grammar certainly is not. The construction of verbs is rather elegant, and various verbs, adjectives and nouns are related in subtly elegant ways. To pick one example, “kugula” is “to buy” and “kugulitsa” is “to sell”.

However, there is one cluster of homonyms in Chichewa that is definitely an area where the language is limited, and is fairly confounding to me as a researcher. I am referring of course to “kwambiri”. It means both “a lot” and “very much”. But colloquially, either it or the adjective “-mbiri” seem to be the most common way to say “more”, “the most”, and “too much”. To pick one example of how this has tripped me up, it has meant that when I was writing survey questions for a project about vaginal drying practices, we couldn’t distinguish between a woman’s vagina being “very wet” and “too wet”, which is kind of central. On another survey, we had to totally rephrase questions about people’s most preferred time to receive income.

I’d imagine this is similar to Spanish speakers trying to translate survey questions that rely on “ser” and “estar” (which are two different senses of “to be”) for into English. Direct translation is often possible, but sometimes things are virtually untranslateable. It also speaks to a broader issue with surveys done in other countries: the fact that your survey questions have been copy-edited, field-tested and validated means almost nothing, because the actual questions your respondents will answer are the translated versions, and those will often be very different.

I am married to a Zambian and I have learned to speak the chinyanja they speak in Lusaka and Livingston. Resources on chinyanja seem hard to find, thank you for the resources you are providing here.

I have seen maningi meaning too much, while kwambili means a lot.

I.e. “Zikomo kwambili.” Sorry the spelling is different, that’s how they spell and say it in Lusaka.