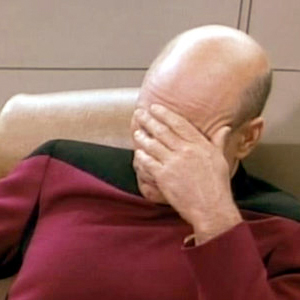

This past weekend I went up M3 to Liwonde National Park for a day and a half. As proof, here is me with some hippos:

I got there by hitching a ride with Brigitte Zimmerman, an awesome political science PhD student from UCSD who I met at WGAPE. Brigitte is here doing her own dissertation research, and was spending the weekend with three other female friends. Liwonde is maybe a 45-minute drive from Zomba, and we were stopped by police more times during that drive than I have ever been in all the time I’ve driven a vehicle here (several weeks).

Nothing happened at any of the stops, which to be honest are fairly routine on the roads here, but it got me thinking. An informal survey indicates that there’s a definite gender discrepancy at play here: women are stopped more often than men, and white men are stopped least of all. The traffic police here are often looking for fines; maybe they think women are more likely to just pay a dubious fine instead of arguing.

So this whole time I’ve been playing with loaded dice, and hardly realized it. This makes me wonder what other subtle benefits I’ve gotten here as a result of my race and gender. It would surprise me very little if I got better prices, at least in terms of initial offers.