Paolo Abarcar has a new post where he uses the example of a study of bloodletting to explain why randomized trials are important for answering questions in economics and development. The actual study he cites has a number of problems that can be attributed to the limited development of science back in 1835 – for example, it was an observational study, and the treatment was not randomized, meaning that potentially ceteris non paribus est.

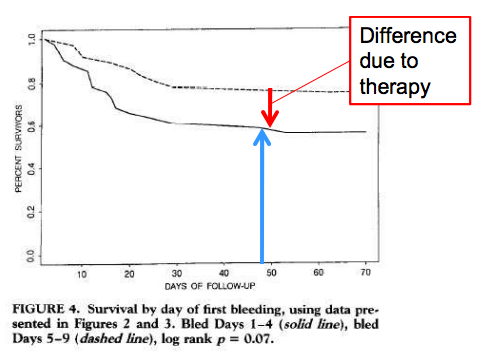

But the bigger problem is highlighted by the caption of the graph above, which presents the main results of the study. There is no control group here – both groups received bloodletting, with the only difference being when it was done. Bloodletting was the standard of care – it was so confidently known to work that it was standard medical practice, and it would have been unconscionable to not provide it. Hence both groups in the study were bled.

This is common practice today, minus the part where we therapeutically cut people open and let them bleed. Medical experiments are expected provide the control group with the standard of care (whatever we typically provide to patients), while the treatment group also gets whatever is being studied. This is usually fine from an empirical and ethical standpoint: we almost always want to compare our treatment to the status quo. There are two kinds of situation where it is not. The first is a practice that I have always been uncomfortable with, which is the importation of developed-world standards of care into developing countries. This often makes the results meaningless, since we are comparing people receiving a realistic treatment to a group that is receiving care that would never be provided in the absence of the study. It also treats people who are selected into the study as more ethically valuable than other people who live in the study site.

The second is a possibility I hadn’t really considered before: what if our standard of care is actively harmful? If it is sufficiently bad, then it could mask any potential benefits of the treatment (remember, the treatment group typically gets standard of care + the treatment). Imagine if bloodletting were still the standard of care: it killed enough people that even effective treatments, in combination with intentionally cutting people open and removing their blood, might look like they didn’t work. Not to mention the fact that we would be actively killing many patients.

I am unsure how big of a problem I think this is. In social science, we don’t usually provide anything to the control group in our studies, which mitigates the extent of the problem. Most medical treatments in the developed world have been studied via randomized experiments, but in developing countries there are lots of standard practices that seem to be somewhere between dubious and actively harmful. For example, the standard of care in Lira appears to be to treat people with headaches and fevers for malaria irrespective of whether they actually have it, with untold consequences for medication compliance and drug resistance.

Perhaps it’s better to talk to doctors about this no? In particular, I’d like to read about the practice of clinical trials in developing countries. I had a conversation the other day with a doctor, and she said, clinical trials here are almost non-existent since patients had to pay for them, usually. Not sure how this extends to other countries though.