Planet Money just finished an amazing eight-part series on how t-shirts are made, centered around following a shirt they are selling (men’s women’s). You can find all the episodes on their podcast’s webpage or by pulling up their podcast on your smartphone. I strongly recommend you listen to the whole thing starting from Part 1 (link). They’re each only around 20 minutes long, and they might be the best reporting on microeconomics, ever. I found that the series challenged a lot of my prior notions about how the garment industry works, and that’s even with a relatively strong base of knowledge.

One theme of the series was that t-shirts are now made in Bangladesh because that is the cheapest place in the world to make them. In the segment on t-shirt factories in Bangladesh, they note that the country recently raised its minimum wage. The consensus among industry experts was that this would end up just raising prices slightly for the end consumer. This would then lead to more income for garment workers in Bangladesh, which sounds like an unmitigated good.

What’s missing from this story is the history of globalized garment manufacture, which has always had the feature that production moves to the cheapest possible place. Indeed, Planet Money discusses one of the most dramatic such moves, which was when production moved from South Korea to Bangladesh because quotas were tightened on Korean-made t-shirts. This move was actually spearheaded by Korean businessmen who actively sought out Bangladeshi partners to start factories in the other country. The argument about the current change in costs is that Bangladesh is as cheap as it gets. There is no place else to go that is cheaper (although they do allude to Cambodia being competitive on costs)

I’m not sure that’s the whole story. Sure, no other country currently offers lower costs of production right now. But when t-shirt manufacture moved to Bangladesh, it didn’t offer lower costs either. What it did offer was lower wages . And despite what NPR might tell you, Bangladesh does not have the lowest wages in the world. According to the World Bank’s excellent PovcalNet tool (which I found via this CSAE blog post), there are 15 countries that have lower average incomes than Bangladesh, based on the most recent available household survey data. This is a decent proxy for having lower wages – made more compelling by the fact that all 15 said countries have higher poverty rates than Bangladesh, meaning that they have lots of people at the low end of their income distributions.

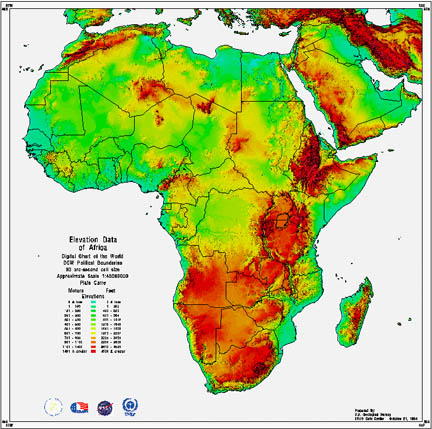

The other thing those countries have in common? All 15 are in Africa. The rise in wages in Bangladesh creates an opportunity for other lower-cost players to step in, and Africa is home to essentially all of them. This opportunity would only really accrue to countries with the ocean ports necessary to participate in the global manufacturing economy, so Liberia, Madagascar, Tanzania, Nigeria, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, and Guinea-Bissau are legitimate candidates. The other 8 possibilities are out of luck, unless road and rail transit improve drastically, or we do something crazy like building a set of canals into the heart of Africa.

This version of the future doesn’t have to end disastrously for Bangladesh, either. Remember, Bangladesh got its start not just by gaining the low-cost lead from South Korea, but also because Korean companies went to Bangladesh to invest there. And South Korea’s fate, after that point, was to continue its spectacular rise into the ranks of the world’s richest countries. This could be the kickstart Bangladesh needs to make a move up the value chain. There are risks: some Bangladeshis will probably lose jobs, for example, especially in the short run, but the large numbers of currently un- and under-employed Africans who would stand to benefit are jut as deserving of our sympathies.

I have no way of knowing whether this is the future we’ll actually end up with, but if I were in the t-shirt business, I wouldn’t settle for keeping my manufacturing in Bangladesh and just accepting higher costs. I would be looking at making clothes on the continent with the lowest wages in the world, which faces the exact same tariff and quota structure as Bangladesh. A continent with a huge number of jobless people who would benefit hugely from more jobs, which happens to have an economy that is growing faster than anyplace else in the world. I would be looking at Africa.