A friend recently sent me the following Actual Advice Mallard, containing a strategy for buying airline tickets that is the hot new thing on the interwebs:

A link from Chris Blattman’s blog indicates that the source of this claim is most likely this reddit post by /u/Valendr0s, who claims experience working in airline ticket pricing and was rewarded with reddit gold (worth $4) for his comment. So this is widely seen as a useful fact, and taken at face value. And I don’t believe it for one second.

My skepticism is motivated by two factors: 1) theory, from my perspective as an economist-in-training, and 2) evidence, from the fact that my mother works for the world’s largest airline and the related fact that I am cheap as hell.

Theoretically, what are airlines trying to do when they vary their prices? Well, probably a lot of things, but most importantly they’re trying to price discriminate. This means separating their customers into categories by how much they’re willing to pay for tickets, and charging them different prices. A simple case of price discrimination happens at movie theaters, which give discounts to students and seniors, both of whom tend to have less income than middle-aged adults.

The classic example of price discrimination for airlines is to charge more for a roundtrip ticket that returns on a Friday than one that returns on the following Sunday or Monday. Why? Business travelers don’t want to spend their weekends away from home, and tourists do. Since business travelers don’t care as much about the cost of their ticket, this price structure can extract more profit out of the market by dividing it. If you charged the same price, then you could either charge a low price tourists will pay (and lose out of extra profit from business travelers) or a high price to gouge business travelers (and lose out on all the sales to tourists). Charging two different prices is the best of both worlds.

How else can airlines price discriminate? I’ve often suspected that the seemingly-random fluctuations in ticket prices over short periods of time are part of another price discrimination strategy. For simplicity, let’s say the market comprises 50 cheap people like me, and 50 normal folks who don’t want to waste their time shopping. Normal people will happily pay the typical market price of $100 for a ticket, but cheap people won’t, they’ll shop around or reconsider if the price is above $40. The two groups are otherwise identical, so there’s in principle no way to differentiate them. If the airline charges $100/ticket, only the normal people buy tickets and it makes $5000.* If it charges $40/ticket, everybody jumps on the tickets and it makes $4000. It seems like there’s no way to do better.

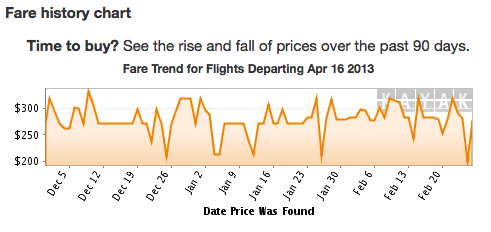

But maybe there is: the airline could randomly offer a $60 discount, 10% of the time. If it does this, then it makes 45*$100+5*$40=4700 from the normal people, who will take either price they see. The cheap people (e.g. me) will hit reload on kayak.com until they see the price they want. All 50 of them will eventually get the $40 ticket offer, so they pay a total of $2000 and the airline’s total profit is $4700+$2000 = $6700. This approach, which I’ll call “randomized price discrimination” just to give it a name, is much more profitable than either of the two alternatives.

Now, you might object that everyone should keep shopping until they hit the jackpot, but the assumption that some people won’t is potentially quite realistic. First off, consumers would have to realize this is how the system works. If cheap people go to different sites instead of refreshing just one, they might get the discount without knowing why it happened. Second, higher-income people have more reason to value their time, and empirically appear to do so more.

It’s also possible that airlines could do both: offer discounts at random but also try to identify “desperate” passengers. But pure reloads, tracked by cookies, are going to confound the two. We need some data.

I don’t have any data, but what I do have are a couple of strong anecdotes. By virtue of my mother’s employment with Delta, I’ve done the vast majority of my lifetime travel on non-revenue passes. These were free when I was younger, and now are steeply discounted relative to full-fare tickets. The only catch is that when I use them, I fly standby. That’s usually an added benefit: I don’t have to plan ahead and can arrive pretty late to the airport. Every once in a while, though, all the flights are full, occasionally for days on end.

I therefore have a fair bit of experience with the kind of “urgency” that Valendr0s says airlines try to exploit: twice in the past year or so, I’ve ended up with no ticket, already late for something I needed to do, and had to give up on standing by for flight after flight and bite the bullet on a full-fare ticket.

In these situations, I’ve done exactly what the advice mallard discourages: continually hit refresh on travel search websites until I find something cheap. I generally look for roundtrip tickets, which are cheaper than one-way ones,** and move the return date around as I don’t plan to use the second leg.*** Consistent with my theory of randomized price discrimination, I was eventually able to find a ticket discounted by over 50% relative to the median, departing on the same day I bought the ticket. These prices I ended up paying would have been excellent even if I’d bought the tickets weeks in advance. My strategy focused almost solely on repeated searches in the Kayak app for my iPhone.

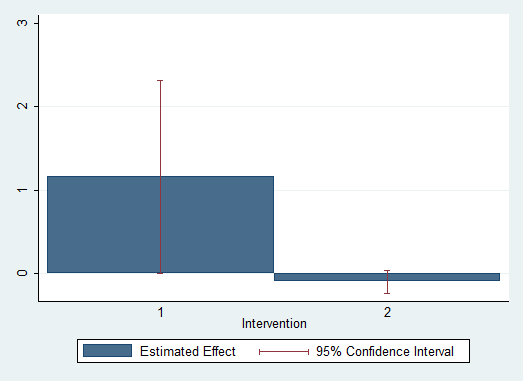

It might still be possible to rescue the Valendr0s model: maybe moving the return date around helps, or maybe there’s something special about the Kayak app. Maybe I “got lucky”, although that seems equivalent to the randomized price discrimination model being true. More important, I only really have two datapoints on this. If I were more ambitious, I might try to set up a data scraper to collect price offers under different conditions (incognito, cookies off, normal) for a range of different flights and days and see if we can sort out these different models.

Failing that, though, I’d actually recommend doing the opposite of what Valendr0s recommends. If you want cheap airline tickets: 1) don’t clear your cookies; 2) hit refresh, over and over; and most important, 3) signal thriftiness, and prove it by revealing the low value you put on your time.

Hat tip: BTK

*I’m ignoring any marginal cost per passenger here (that is, the increased fuel and soft drink costs associated with another person on the plane) but the result doesn’t depend on that.

**I still don’t have a good explanation for why this is the case. My only theory is that it’s a way of price discriminating between more- and less-informed travelers.

***Even if I wanted to use it, I could just pay the change fee later on.