Poor people often have trouble saving money for a number of reasons: the banks they have access to are low-quality and expensive (and far away), saving is risky, and money that they do save is often eaten away by kin taxes. One reason that has featured prominently in theoretical explanations of poverty traps is “temptation spending” – goods like alcohol or tobacco that people can’t resist buying even though they’d really prefer not to. Intuitively, exposure to temptation reduces saving in two ways. First, it directly drains people’s cash holdings, so money they might have saved gets “wasted” on the good in question. Second, people realize that their future self will just waste their savings on temptation goods, so they don’t even try to save.

But how important is temptation spending in the economic lives of the poor? Together with Lasse Brune and my student Qingxiao Li, I have just completed a draft of a paper that tackles this question using data from a field experiment in Malawi. The short answer is: probably not very important after all.

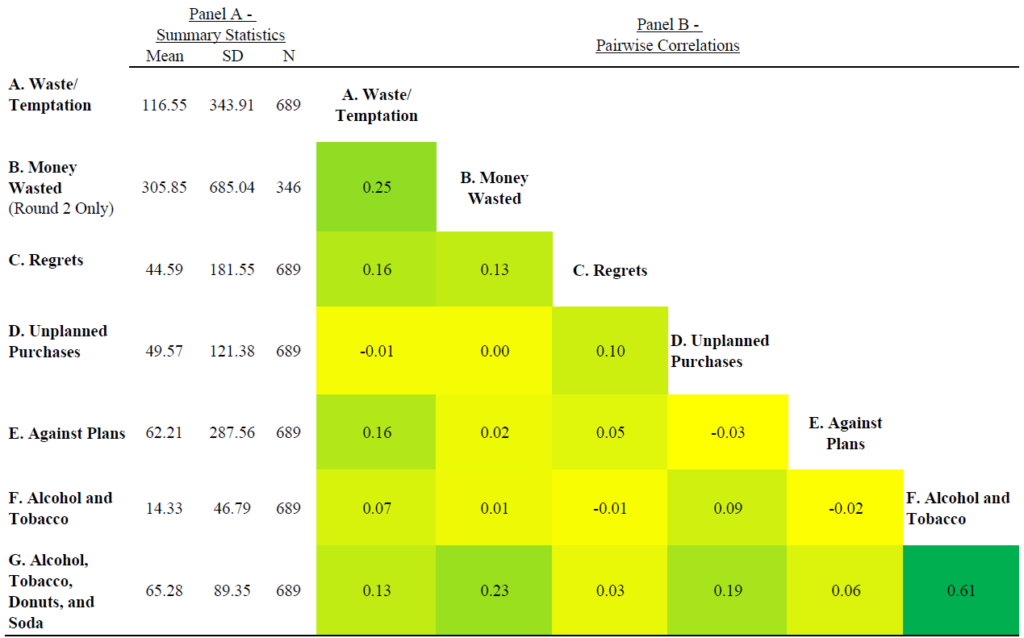

One of our key contributions in the paper is to measure temptation spending by letting people define it for themselves. We do this two ways: first, we allow our subjects to list goods they are often tempted to buy or feel they waste money on, and then match that person-specific list of goods to a separate enumeration of items that they purchased. Second, we let people give the simple sum of money they spent that they felt was wasted. We also present several other potential definitions of temptation spending that are common in the literature, including the alcohol & tobacco definition, and also a combined index across all the definitions. The correlations between these measures are not very high: spending on alcohol & tobacco correlates with spending on self-designated temptation goods at just 0.07:

This is the result of people picking very different goods than policymakers or researchers might select as “temptation goods”. For example people commonly listed clothes as a temptation good, whereas alcohol was fairly uncommon.

We also show that direct exposure to a tempting environment does not significantly affect spending on temptation goods – let alone downstream outcomes. Our subjects were workers who received extra cash income during the agricultural offseason as part of our study. All workers received their pay at the largest local trading center, and some were randomly assigned to receive their pay during the market day (as opposed to the day before). This was the most-tempting environment commonly reported by the people in our study. Getting paid at the market didn’t move any of our measures of temptation spending and we can rule out meaningful effect sizes.

Why not? We go through a set of six possible explanations and find support for two of them. The first is substitution bias: the market where workers were paid was just one of several in the local area, some of which operated on the day the untreated workers were paid. It was feasible for them to go to the other markets to seek out temptation goods to buy, effectively undoing the treatment. This implies a very different model of temptation than we usually have in mind: it would mean that the purchases tempt you even if they are far away and you have to go seek them out.*

The second is pre-commitment to spending plans. If workers can find a way to mentally “tie their hands” by committing to spend their earnings on specific goods or services, they can mitigate the effects of temptation. We see some empirical evidence for this: the effects of the treatment are heterogeneous by whether workers have children enrolled in school. School fees are a common pre-planned expense in our setting; consistent with workers pre-committing to pay school fees, we see zero treatment effects for workers with children in school, and substantial positive effects for other workers.

Both of these explanations suggest that temptation spending is much less of a policy concern than we might have thought. The first story implies that specific exposure to a tempting environment may not matter at all – people will seek out tempting goods whether they are near them or not. The latter suggests that people can use either mental accounting or actual financial agreements to shield themselves from the risk of temptation spending.

There is much more in the paper, “How Important is Temptation Spending? Maybe Less than We Thought” – check it out by clicking here. Feedback and suggestions are very welcome!