I recently returned from a two-week* trip to Malawi to oversee a number of research projects, most importantly a study of savings among employees at an agricultural firm in the far south of the country. For the first time in years, however, I also took the time to visit other parts of Malawi. One spot I got back to was the country’s former capital, Zomba, where I spent an extended period in graduate school collecting data for my job market paper. This was my first time back there in over four years.

The break in time between my visits to the city made it possible to see how the city has grown and changed. I was happy to see signs of growth and improvement everywhere:

- There are far more guest houses than I recall.

- The prices at my favorite restaurant have gone up, and their menu has expanded by about a factor of five.

- They finally got rid of the stupid stoplight in the middle of town. I used to complain that traffic flowed better when it was broken or the power was out; things definitely seem to work better without it. (Okay, this might not technically be economic development but it’s a huge improvement.)

- Whole new buildings full of shops and restaurants have gone up. I was particularly blown away to see a Steers. In 2012, I could count the international fast-food chain restaurants in Malawi on one hand. This Steers is the only fast-food franchise I’ve seen outside of the Lilongwe (the seat of government) and Blantyre (the second-largest city and commercial capital).

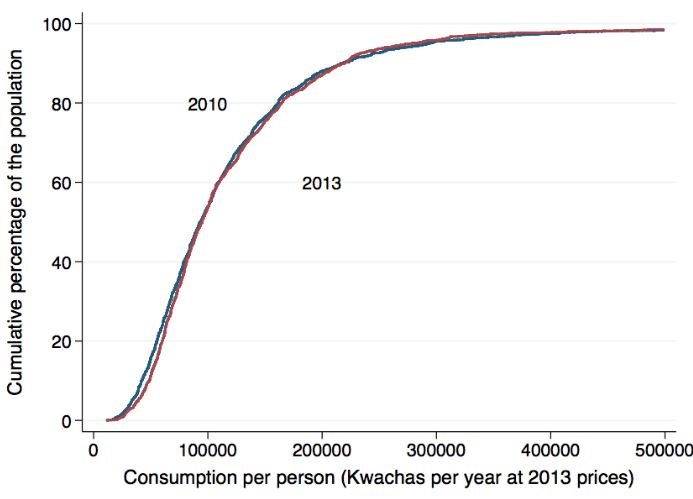

What’s driving this evident economic growth? It’s really hard to say. Zomba is not a boomtown with growth driven by the obvious and massive surge of a major industry. Instead, it seems like everything is just a little bit better than it was before. The rate of change is so gradual that you probably wouldn’t notice it if you were watching the whole time. Here’s a graph that shows snapshots of the consumption distribution for the whole country, in 2010 (blue) and 2013 (red), from the World Bank’s Integrated Household Panel Survey:

For most of the distribution, the red line is just barely to the right of the blue one.** That means that for a given percentile of the consumption distribution (on the y-axis) people are a tiny bit better off. It would be very easy to miss this given the myriad individual shocks and seasonal fluctuations that people in Malawi face. It’s probably an advantage for me to come back after a break of several years – it implicitly smooths out all the fluctuations and lets me see the broader trends.

These steady-but-mysterious improvements in livelihoods are characteristic of Africa as a whole. The conventional wisdom on African economic growth is that it is led by resource booms – discoveries of oil, rises in the oil price, etc. That story is wrong. Even in resource-rich countries, growth is driven as much by other sectors as by natural resources:

Nigeria is known as the largest oil exporter in Africa, but its growth in agriculture, manufacturing, and services is either close to or higher than overall growth in GDP per capita. (Diao and McMillan 2015)

Urbanization is also probably not an explanation. Using panel data to track changes in individuals’ incomes when they move to cities, Hicks et al. (2017) find that “per capita consumption gaps between non-agricultural and agricultural sectors, as well as between urban and rural areas, are also close to zero once individual fixed effects are included.”

So what could be going on? One candidate explanation is the steady diffusion of technology. Internet access is more widely available than ever in Malawi: more people have internet-enabled smartphones, and more cell towers have fiber-optic cables linked to them. While in Malawi I was buying internet access for $2.69 per gigabyte. In the US, I pay AT&T $17.68 per GB (plus phone service but I rarely use that). Unsurprisingly, perhaps, better internet leads to more jobs and better ones. Hjort and Poulsen (2017) show that when new transoceanic fiber-optic cables were installed, the countries serviced by them experienced declines in low-skilled employment and larger increases in high-skilled jobs. Other technologies are steadily diffusing into Africa as well, and presumably also leading to economic growth.

Another explanation that I find compelling is that Africa has seen steady improvements in human capital, led by massive gains in maternal and child health and the rollout of universal primary education. Convincing evidence on the benefits of these things is hard to come by, but one example comes from the long-run followup to the classic “Worms” paper. Ten years after the original randomized de-worming intervention, the authors track down the same people and find that treated kids are working 12% more hours per week and eating 5% more meals.

But the really right answer is that we just don’t know. Economics as a discipline has gotten quite good at determining the effects of causes: how does Y move when I change X? The causes of effects (“Why is Y changing?”) are fundamentally harder to study. Recent research on African economic growth has helped rule out some just-so stories – for example, it’s not just rents from mining, and even agriculture is showing increased productivity – but we still don’t have the whole picture. What we do have, however, is increasing evidence on levers that can be used to help raise incomes, such as investing in children’s health and education, or making it easier for new technologies to diffuse across the continent.

You left out the most important information: what did you order at Steers and wasn’t it awesome? Also, there is more than one cappuccino joint in Zomba now. So fancy!

I had a Spicy King Steer with a passion Fanta and it was amazing.

Cappuccinos – at African Heritage & where else? Clearly I missed a place!

Interesting narrative