In an article on Slate, Jenny Trinitapoli and Alexander Weinreb argue that the decline in HIV incidence in Africa can be attributed to religious leaders preaching a pragmatic message of sexual morality and caution. As evidence, they cite different behaviors and beliefs among congregants at churches that discuss AIDS and sex compared with the rest of the population, based on their own research in Malawi.

This idea is consistent with some of my own personal experiences in Malawi, but the first question that comes to mind is what kind of person chooses to attend one of these particular churches, and why they do it. Church membership is anything but random, and it’s conceivable that self-selection is driving a lot of the differences they are picking up. Even if that’s not an important factor, there’s also the issue of the epidemiological importance of those affected by these religion-based messages: HIV epidemics are driven by high-activity subpopulations, who don’t strike me as particularly likely to show up at church. Instead, I’d assume they are more like the people Trinitapoli and Weinreb describe in this passage:

Many of us drink in the comfort of our own homes (often accompanied by our loving partners). But consumption of alcohol across Africa tends to be more public and to occur in places that provide opportunities for unsafe sex: Women working at bars and bottle shops often double as prostitutes.

Another question is what other factors should also receive credit for any decline in HIV incidence. Mother-to-child transmission prevention efforts now often involve putting HIV-positive mothers on permanent antiretroviral therapy, which we now know to have pretty huge benefits in terms of reducing HIV transmission.

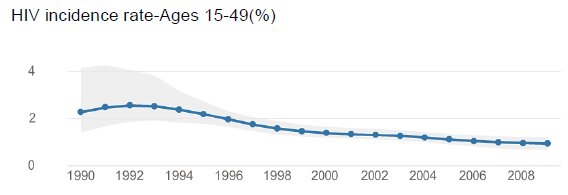

I’m also curious about their claims about changes in sexual behavior and HIV incidence – the authors cite incidence declines for Africa as a whole, but those don’t match what I understand to be the case for Malawi in particular. UNAIDS estimates show the incidence (new cases) to be fairly steady at 1% of the overall population.

Maybe you can read a 25% (not percentage-point) decline since 2001 off that graph if you squint at it, but that would be something like 1.25% to 1%, a pretty small change in actual magnitude. If you do a back-of-the-envelope calculation, with a life expectancy of 10 years after infection, 1% incidence is consistent with a stable prevalence of 10% of the population. We can take this a step further: imagine following a cohort of 15-year-olds over time. Each year, 1% contracts HIV, so that the average across all people 15-49 is 1%. While increased mortality among HIV-positive people will keep the prevalence at any given time near 10%, by the time people reach 49 their total chance of HIV infection is 34%.* One in three. I’m not sure that it’s time to figure out whose needs to get credit for our huge success yet.

This isn’t to say that the idea isn’t really valuable – based on what they’re finding, I think somebody should try a pretty simple experiment where the treatment is training preachers on the sex and AIDS messaging that appears to be working.

FYI – Jenny and Alex have a book that came out with Oxford Press on this very topic (the Slate article just touches the surface): _Religion and AIDS in Africa_. I’m assigning it in a seminar next spring, so hope to read it this summer!